King Lear

Well, I must admit that I feel a bit bad: you were likely not in a great mood after UNC lost on Friday, and then you had to encounter this deeply pessimistic play that veers on the edge of anarchy at moments. But maybe this actually felt right over the weekend! I want to start not, as usual, with my thesis, but with two quotes. Follow along and see if you can begin to guess what it is that I’m hoping for us to focus on, with the caveat that this will not be our only emphasis in discussion.

So first, turn with me to Act 3, Scene Four, at line 28. We’ll go through this slowly because there’s a lot going on.

Lear: Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? Oh, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just. (3.4.28-36).

What is Lear essentially saying/regretting in this moment? What is he, more importantly, learning about himself?

Now I’m going to ask you to pair this passage with one that follows soon after in the same scene. Again, try to guess where I’m going with my thesis for this play.

Lear: Thou wert better in a grave than to answer with thy uncovered body this extremity of the skies. Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou ow’st the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Ha! Here’s three on’s are sophisticated; thou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings! Come, unbutton here. (3.4.100-108).

Okay, so let’s walk through this passage. Recall that Lear is in the middle of a violent storm, and he is encountering Edgar, disguised as poor Tom, who has only what we can assume is a loincloth or something covering him. And yet here Lear is confronted with an image of humanity that he has not ever accessed before, the very lowest forms of humanity. So what do you think is going on here? What is Lear learning at this moment? And finally, can anyone guess what I’m thinking about for today’s thesis?

If you guessed human suffering or simply human nature, you’d be right. Lear has to have everything literally stripped away from him in order to learn something central about those individuals who have not been flattered or coddled with “pomp.”

Thus from the very narrow, we might say claustrophobic, atmosphere of Othello, we now come to the wide expanse of King Lear. This play considers almost everything—human perfectibility, familial relationships, politics—on a cosmic scope. Indeed, the word “nature” appears more in King Lear than in any other Shakespearean play. Figures often question a universe that seems unresponsive or even malignant towards humans. King Lear is a deeply pessimistic play—unsurprising given that it’s a tragedy. Nonetheless, the very lengths of its depiction of human suffering strike us, perhaps, as so very painful because we never get an easy answer to questions of injustice and pain. King Lear is thus also a highly philosophical play, an issue that we are going to explore through the classic, albeit problematic, question of: what is human nature? Are we innately bound for good or evil? What are our obligations to family or kings? What is in a human? What distinguishes a person from an animal? This play probes such questions with an unrelenting critical view.

But before we get to human nature and suffering, I want to talk about something entirely different because it relates to this play’s history. That is, I’m going to spoil the play for you and think about the concept of spoilers. I’ve been thinking about them a lot because I recently watched Jordan Peele’s Us, and was considering how horrific it would be, how it would change so much for an individual, to spoil the movie for them. And I’m also thinking about the processes involved in revision, because Peele did revise the ending to his first film Get Out. Has anyone seen the alternate ending? I won’t spoil that but I encourage you to watch it because it offers an entirely different tone to the film’s conclusions [as a complete side-bar, I’ve also been thinking recently about Peele’s use of comedy in horror and how Shakespeare does the same thing. My supposition is that perhaps the two are in conversation somehow]. I’m not going to spoil any of Peele’s work, but I am going to spoil King Lear for you. Guess what? Almost everyone dies—Lear, Cordelia, the Fool, Edmund, Goneril, Regan, and Gloucester. But why am I spoiling this for you? In part, because with the frame of the title, The Tragedy of King Lear, you were likely expecting something akin to this conclusion given what we have learned about tragedy this semester. Tragedy is about cleansing, doing away with both the evil but also some of the pure in the world so that we can regain a type of middle-ground politically and morally.

I’m also spoiling the play for you because if you were living in Shakespeare’s day, someone would have spoiled the play for you by calling it a tragedy. What I mean here is, most folks were familiar with the King Lear story from its historical sources. And all of the sources provide, believe it or not, a happy ending. And I’m sorry to say that Shakespeare radically rewrites that happy ending. The first recorded account is in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae [The History of the Kings of Britain] (c.1136). And Raphael Holinshed follows this source. In both, and in a play titled King Leir that was published in a quarto in 1605, Lear is rescued by Cordelia and her army and rules peacefully until a natural death some two years later.

So imagine this: you’re living in England around the turn of the seventeenth century. You have perhaps read the history of King Lear in Holinshed. Maybe you’ve even seen the play King Leir, which claims to be a chronicle history, and so you’re familiar with the story (though it’s unclear if Shakespeare’s version was written before or after this play. But this is imaginative, so we’ll ignore that point for now). Okay, so then you decide to see how Shakespeare’s acting company represents the story. And you’re on the edge of your seat, even up to those last, final moments when Lear famous says “Look on her, look, her lips, / Look there, look there!” (5.3.316-317), in which the possibility that Cordelia might revive is still an option. And yet, right at this moment, holding the body of his dead daughter, Lear himself dies. Whew. If you were this person in Shakespeare’s day, you would likely be utterly shocked. How could this be possible? Why in the world did Shakespeare rewrite the ending?

Shakespeare’s revision was seen as so unpalatable that the ending was indeed rewritten. A man by the name of Nahum Tate rewrote the play as The History of King Lear, in which, like the original histories, Lear and Cordelia both survive the horrors inflicted upon them and Cordelia marries Edgar, thus bringing the two plots together in a neat symmetry. Incredibly, Tate’s version replaced Shakespeare’s, in large part, until about 1838. Tate also cut the figure of the Fool, a true tragedy in my reading. I’d like for you to keep this history in mind for when we reach the end of the play on Thursday, because it does bear on how we read the sublime and the tragic in this narrative.

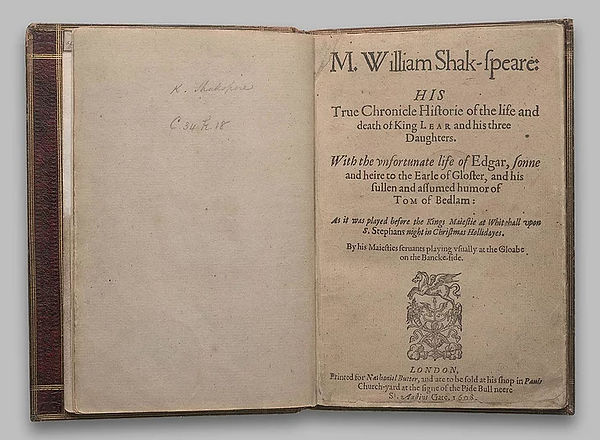

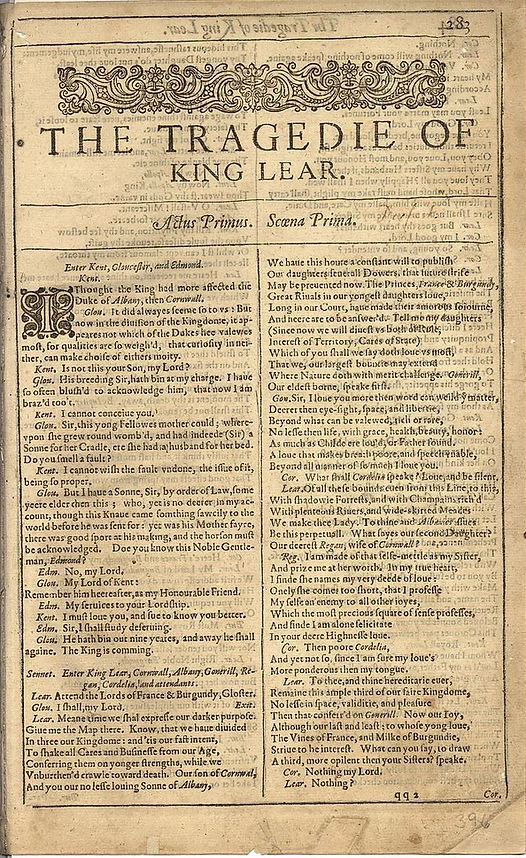

We should also acknowledge that King Lear has a very complicated, but interesting, textual history. It was published as a quarto with the title M. William Shak-speare: HIS True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King LEAR and his three Daughters. With the vnfortunate life of Edgar, soone and heire to the Earle of Gloster, and his sullen and assumed humor of TOM of Bedlam. This quarto appeared in 1608, but the version in the Folio is different in a few significant ways. For example, the ending is slightly different in each version, something we will look at in more detail on Thursday. Editors have resolved this difference in part by presenting a conflated version of the text, borrowing from both the quarto and the Folio, as the editors of our textbook do. But what I will suggest on Thursday is that reading the two endings in particular presents some interesting problems and reminds us that Shakespeare wasn’t the type of author who would simply write brilliant works and then let them alone. No, instead he did revise his works, as you should in your own writing! Keep this in mind too for Thursday.

Unnatural Daughters

Okay, so let’s now return back to my thesis (or is it several theses?) of the play, namely, that this play is questioning what it is that constitutes human nature. And we should add to this the political element. Do humans need society? What is the right way to rule? If you’re at all interested in politics, King Lear is a great case-study, because in large part Shakespeare is exploring the very nature of kingship.

So we might, like many scholars have done, and as Kent does explicitly in the play, criticize Lear’s political decision to divide the kingdom. But we should note that Kent is in on the plan to divide it into three portions, and that this might have worked. With the balance among three different powers, perhaps the kingdom could have reached a type of stasis with three powers in charge. But with two, the play suggests, war will inevitably arise. So perhaps it’s not that Lear is initially at fault, but it’s when he couples emotion, primarily rage, with ruling that he goes astray.

Lear frames his division of the kingdom in terms of both nature and merit. Both qualities or gifts will contend, he claims, in his decision to portion out his land to his three daughters. We should note, however, the irony here, because it is clear that Lear has already in mind what divisions he shall make. Nonetheless, the challenge, set up like the beginning of many fairy-tales, is one that demands flattery or acknowledgement of the rules of courtly behavior in oratorical performance. Thus Lear demands, very publicly, for Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia to declare

Which of you shall we say doth love us most,

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge? (1.1.51-53).

Famously, Cordelia refuses to play this game. She is more idealistic and obviously much more truthful than her sisters. But as we mentioned in a previous class, tragedy deals in absolutes, and Lear cannot stand any qualification of what he believes is due to him. It’s interesting that we witness Lear’s tragic flaw—pride—so very early in this play, almost as if the play is racing to establish the faults of the King in order to dwell in elongated form on not the flaw itself but on the philosophical and passionate consequences of Lear’s irrational dismissal of his one true child. Let’s look at their exchange, keeping in mind that we should also question why Cordelia herself is so unmoving. Why can’t she at least adhere to the conventions of the court in this public setting and give her father what he wants to hear? Why does the play swing so quickly from the “everything” of Goneril and Regan’s speeches to Cordelia’s “nothing”? [We should look to trace, too, this term “nothing” in the play, another highly charged and enigmatic word throughout].

Lear Now, our joy,

Although our last and least, to whose young love

The vines of France and milk of Burgundy

Strive to be interessed, what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters’? Speak.

Cordelia Nothing, my lord.

Lear Nothing?

Cordelia Nothing.

Lear Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again.

Cordelia Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth. I love Your Majesty

According to my bond, no more nor less.

Lear How, how, Cordelia? Mend your speech a little,

Lest you may mar your fortunes.

Cordelia Good my lord,

You have begot me, bred me, loved me. I

Return those duties back as are right fit,

Obey you, love you, and most honor you.

Why have my sisters husbands if they say

They love you all? Haply, when I shall wed,

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty.

Sure I shall never marry like my sisters,

To love my father all.

Lear But goes thy heart with this?

Cordelia Ay, my good lord.

Lear So young, and so untender?

Cordelia So young, my lord, and true.

Lear Let it be so! Thy truth then be thy dower!

For, by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night,

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be,

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity, and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this forever. The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbored, pitied, and relieved

As thou my sometime daughter. (1.1.82-120).

Notice how quickly Lear is prone to anger. He is, we learn very early, a king led by rhetoric and the passions. And yet some have criticized Cordelia here too. Why can’t she perform the basic courtly role required of her? The answer, I want to suggest, is that Cordelia follows the law of nature here, not the law of custom or social requirements. Her gods are truth and plain-speaking, much like Kent. But Lear has been accustomed to flattery for so long, and Goneril and Regan know how to dissemble. Lear, and two of his daughters, understand the value of performance, while Cordelia refuses to play any sort of role besides her true one.

Of course, Lear falsely believes that he can retain the name of the king without the power. But once you strip away military force and all of the divine associations of kingship, you are left with what we began our discussion today with, namely, the unadorned human itself. Lear believes that even without these trappings he can wield absolute power, but Kent reminds him of something poignant and painful: “Thou swear’st thy gods in vain” (1.1.163). Indeed, we might be struck by how godless this world is in King Lear. There are no mediators to ensure justice, something we will see forcibly when we turn to the dual trial scenes in Act 3. Lear will continually swear by the gods, only to have silence or storms in response.

Lear, then, lacks self-knowledge, something that Regan voices directly: “Yet he hath ever but slenderly known himself” (1.1.296-297). And that lack of self-knowledge will be a factor in Lear’s madness. Thus when Goneril first broaches the idea of lessening his train, Lear must confront the fact that he is no longer sole sovereign:

Lear: Does any here know me? This is not Lear.

Does Lear walk thus, speak thus? Where are his eyes?

Either his notion weakens, or his discernings

Are lethargied—Ha! Waking? ’Tis not so.

Who is it that can tell me who I am?

Fool: Lear’s shadow. (1.4.223-228).

The Fool’s response is apt and yet so painful. Lear, for the first time encountering a check to his powers, responds by turning to Nature herself. And in a moment we will consider who else relies on Nature, but I want us to end this part of the discussion by looking at Lear’s first of many curses against his daughters. To Goneril he disclaims:

Lear: Hear, Nature, hear! Dear goddess, hear!

Suspend thy purpose if thou didst intend

To make this creature fruitful!

Into her womb convey sterility;

Dry up in her the organs of increase,

And from her derogate body never spring

A babe to honor her! If she must teem,

Create her child of spleen, that it may live

And be a thwart disnatured torment to her!

Let it stamp wrinkles in her brow of youth,

With cadent tears fret channels in her cheeks,

Turn all her mother’s pains and benefits

To laughter and contempt, that she may feel

How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is

To have a thankless child! (1.4.274-288).

The Natural

In our investigation of nature, we also have to grapple with a complex term in Shakespeare’s day: the natural (and its negative form, the unnatural). The word has many meanings in King Lear, which build off of each other and complicate our image of human relationships and human-to-nature bonds in the play. Natural could mean, for example, illegitimate, as it does when referring to Edmund as the “natural” son of Gloucester. He is marked, at the very beginning of the play, by his natural status as a bastard. Unlike Iago, Edmund’s motives are quite clear—he has been labeled a “natural” son from no fault of his own and works to disinherit his legitimate brother in order to gain respect and power. Indeed, Shakespeare forefronts the natural status of Edmund. Let’s look at this opening exchange between Kent and Gloucester, in which the language could be read as excessively dismissive of Edmund:

Kent Is not this your son, my lord?

Gloucester His breeding, sir, hath been at my charge. I have so often blushed to acknowledge him that now I am brazed to’t.

Kent I cannot conceive you.

Gloucester Sir, this young fellow’s mother could; whereupon she grew round-wombed and had indeed, sir, a son for her cradle ere she had a husband for her bed. Do you smell a fault?

Kent I cannot wish the fault undone, the issue of it being so proper.

Gloucester But I have a son, sir, by order of law, some year elder than this, who yet is no dearer in my account. Though this knave came something saucily to the world before he was sent for, yet was his mother fair, there was good sport at his making, and the whoreson must be acknowledged. (1.1.8-24).

It is Kent who addresses the fact of Edmund’s presence, leading us to question whether Gloucester would have introduced him had he not been prompted to by Kent. And Edmund must silently hear all of the negative, erotic language surrounding his conception. It is not, for Edmund, a favorable introduction to a nobleman, and one gets the sense that this is how he is usually introduced to others.

Edmund himself believes that Nature is his only true guide. His opening soliloquy establishes that for him Nature is a force—unlike the gods or any form of social custom—that can be a co-author or co-actor in deciding his fate. But Edmund does not really believe in fate, and in this he is a stark rationalist.

Thou, Nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me,

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? Wherefore base?

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true,

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With base? With baseness? Bastardy? Base, base?

Who in the lusty stealth of nature take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth within a dull, stale, tired bed

Go to th’ creating a whole tribe of fops

Got ’tween asleep and wake? Well, then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land.

Our father’s love is to the bastard Edmund

As to th’ legitimate. Find word, “legitimate”!

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall top th’ legitimate. I grow, I prosper.

Now, gods, stand up for bastards! (1.2.1-22).

I actually want us to see Riz Ahmed’s rendition of this speech because I think he captures the angst and anger of Edmund perfectly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-epojal7nE. What do we make of Edmund’s alignment with Nature here as his goddess? What in this reading is the alternative to Nature? It’s social custom and the idea that human-derived institutions, like marriage, have some sort of hold on us.

Edmund’s notion of Nature, however, differs from his father’s. I want us to look at this difference in more detail because it reveals something at the core of this play about how individuals are to gain knowledge and certainty in an uncertain cosmos. Gloucester, for example, believes that we can gain some type of knowledge from reading the heavens, while Edmund disclaims against any type of philosophical or scientific understanding:

Gloucester: These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us. Though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds itself scourged by the sequent effects. Love cools, friendship falls off, brothers divide; in cities, mutinies; in countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond cracked twixt son and father. This villain of mine comes under the prediction; there’s son against father. The King falls from the bias of nature; there’s father against child. We have seen the best of our time. Machinations, hollowness, treachery, and all ruinous disorders follow us disquietly to our graves. Find out this villain, Edmund; it shall lose thee nothing. Do it carefully. And the noble and truehearted Kent banished! His offense, honesty! ’Tis strange. [Exit.]

Edmund: This is the excellent foppery of the world, that when we are sick in fortune—often the surfeits of our own behavior—we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and stars, as if we were villains on necessity, fools by heavenly compulsion, knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance, drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence, and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish disposition on the charge of a star! My father compounded with my mother under the Dragon’s tail and my nativity was under Ursa Major, so that it follows I am rough and lecherous. Fut, I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing. (1.2.106-136).

But what’s ironic is that Gloucester is ultimately right. Edmund is treacherous and, as we shall see on Thursday, also sexually liberal. And the late environmental responses have accurately foretold of all these divisions. We might, as modern individuals, side with Edmund here. But I think it’s important for us to consider Gloucester’s perspective as a serious one.

The Fool and Madness

Related to this discussion is the fact that the Fool can peer accurately into human nature and anatomize the foibles of his master and others. This Fool is one of the more fascinating characters in the play, and I’m hoping we can spend time today and on Thursday on his character. When we are introduced to him, he provides us with a searching analysis of King Lear’s own folly. He says to Kent, “Sirrah, you were best take my coxcomb.” When Kent asks why, he explains, “Why? For taking one’s part that’s out of favor. Nay, an thou canst not smile as the wind sits, thou’lt catch cold shortly. There, take my coxcomb. Why, this fellow has banished two on’s daughters and did the third a blessing against his will. If thou follow him, thou must needs wear my coxcomb.—How now, nuncle? Would I had two coxcombs and two daughters” (1.4.97-103). To Lear’s question, the Fool responds “If I have them all my living, I’d keep my coxcombs myself” (1.4.105-106). In his jests with Lear, the Fool identifies the King’s faults, to which Kent accurately observes “This is not altogether fool, my lord” (1.4.149). But touchingly, this all-seeing Fool stays by Lear’s side, particularly when Lear’s wits start to turn.

So let’s talk about Lear’s madness, which relates to today’s thesis in that through losing everything, including his wits, Lear undergoes an important lesson. Like the Fool, once Lear is mad he can see into things more clearly, as we saw as we began our discussion today. And Lear identifies the movement from sanity to madness throughout. Thus even in Act 1, Scene 5, he cries “Oh, let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven! / Keep me in temper; I would not be mad!” (1.5.45-46). And yet “sweet heaven” does not respond save providing a harrowing tempest, a type of negative answer to Lear’s plea.

Part of the problem is that, as an old man, Lear’s very masculinity is called into question. He often cries when thwarted, and when he sees Kent in the stocks he exclaims:

Oh, how this mother swells up toward my heart!

Hysterica passio, down, thou climbing sorrow!

Thy element’s below. (2.4.55-57).

In Othello, the titular character is shocked that his actions have not produced a cosmic response. In King Lear, however, the environment echoes the King’s inner turmoil through the storm. In fact, I want us to look at the moment when the storm begins, because it’s a clever mirroring of the inner and the outer self in the play. Lear, being denied his followers, turns to his two duplicitous daughters, accusing them of hypocrisy in their demands. The speech is a famous one, and rightly so, for it points us back to the question of what constitutes the human over and above the animal.

Lear: Oh, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. Thou art a lady;

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st,

Which scarcely keeps thee warm. But, for true need—

You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need!

You see me here, you gods, a poor old man,

As full of grief as age, wretched in both.

If it be you that stirs these daughters’ hearts

Against their father, fool me not so much

To bear it tamely; touch me with noble anger,

And let not women’s weapons, water drops,

Stain my man’s cheeks. No, you unnatural hags,

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall—I will do such things—

What they are yet I know not, but they shall be

The terrors of the earth. You think I’ll weep;

No, I’ll not weep. [Storm and tempest.]

I have full cause of weeping; but this heart

Shall break into a hundred thousand flaws

Or ere I’ll weep. Oh, Fool, I shall go mad! (2.4.266-288).

And when we do see Lear again, at the beginning of Act 3, Scene 2, it does appear that he is indeed, mad. Though notice that he still retains some sense of self or of pity, or perhaps his madness enables him to gain that pity. To see what I mean, let’s compare the opening of the scene to another moment that follows soon after.

Lear: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drenched our steeples, drowned the cocks!

You sulfurous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’th’world!

Crack nature’s molds, all germens spill at once

That makes ingrateful man! (3.2.1-9).

No longer bound, or rather betrayed by, the social customs of duty and honor, Lear wishes to undo nature herself, to bring about pure chaos since he can no longer understand the world in which he lives. Nonetheless, he is brought back to the present and to his present needs by others. In one of the most moving moments of the play, Lear forgets his pain and turns to the shivering Fool:

Lear: My wits begin to turn.

Come on, my boy. How dost, my boy? Art cold?

I am cold myself.—Where is this straw, my fellow?

The art of our necessities is strange,

And can make vile things precious. Come, your hovel.—

Poor fool and knave, I have one part in my heart

That’s sorry yet for thee. (3.2.67-73).

Ironically, it is in this hovel that Lear encounters the image of pure madness (though we know that this is indeed Edgar only disguised as poor Tom. But this image of the madman prompts Lear’s speech on “unaccommodated man.”

The Double Plot

This is the first time we’ve encountered a true double-plot in Shakespeare, something he added to the historical narrative of Lear. So I’d like for you to actually mark this out for us, paying careful attention to the last scene we read for today, namely Act 3, Scene 7. As a warning, this is a harrowing scene. But focus on how Gloucester’s plight both diverges from and yet parallels Lear’s.